Trade Policy Review: Responses of Helmut Scholz, MEP, Coordinator INTA for THE LEFT (GUE/NGL)

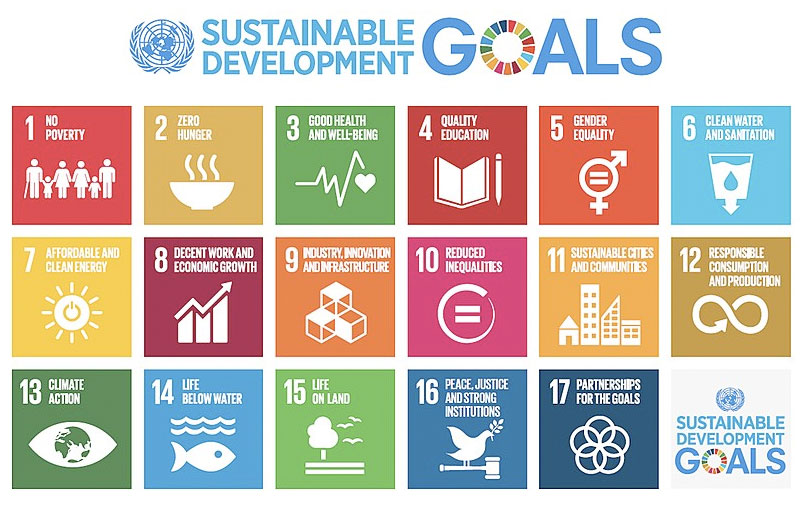

Die Umsetzung der UN-Nachhaltigkeitsziele (SDG) bis 2030 müsse zum Maßstab für den Erfolg der europäischen und internationalen Handelspolitik werden. Das fordert der Europaabgeordnete und handelspolitische Sprecher der Linksfraktion im Europäischen Parlament, Helmut Scholz, in seiner Stellungnahme zur Überprüfung der Handelspolitik der EU (Trade Policy Review 2020).

Hintergrund: Im Juni hatte die Europäische Kommission eine Überprüfung der Handels- und Investitionspolitik der EU eingeleitet. In einem bis 15. November laufenden Konsultationsprozess konnten sich Industrie, Sozialpartnern, Zivilgesellschaft und Bürger*innen beteiligen. Die Kommission hatte dazu einen Katalog mit 13 Fragen vorgegeben. https://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2020/july/tradoc_158864.pdf

Trade Policy Review 2020 - Public Consultation

Responses of Helmut Scholz, Member of the European Parliament

Coordinator Committee on International Trade (INTA) for THE LEFT (GUE/NGL)

Question 1: How can trade policy help to improve the EU`s resilience and build a model of open strategic autonomy?

Resilience is not achieved, improved and maintained by addressing conventional business factors alone. Resilience can be achieved only if embedded in a successful strategy to achieve the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030. This has to happen at a time of an accelerated deep change of global economic structures and the respective international framing of value and supply chains and efforts of states in regulating the development of the markets. That requires a paradigm shift.

We need to measure the success of trade policy no longer by GDP growth figures and profits for companies based in the EU. Trade Policy must contribute to advance societies globally and the indicators for that are provided by the SDGs. Achieving the SDGs translate directly into increasing resilience. Resilience must be achieved in cooperation with our neighbours and global partners, and not at their expense. A modernised trade policy of the European Union can and should help to achieve this.

Compared to other world regions, the Union is still highly competitive and self-reliant, even if further digitalization of the entire economic and social functioning of societies raises additional challenges for the industries and services in the EU. Looking back to recent experiences we can summarize, that the opportunities offered for example by the Chinese market for exports of quality products from the EU have remarkably reduced the damage caused by the 2008 melt-down of the global financial services market and the subsequent collapse of consumer demand in the U.S. and other severely affected economies. The importance of the export markets in China, Japan and the ASEAN region has until today constantly increased. Therefore, trade and economic co-operation with China and other Asian economies, as well as the re-shaping of commercial cooperation with countries on the African continent, also within AfCFTA on a fair partnership basis, will be the Union’s chance for breathing life into our economy after the pandemic.

Not all sectors and not all Member States are equally able to harvest these opportunities. To put it simple, the demand of a growing number of middle class and upper middle class consumers in Asia is for products with a high quality image. Established brand names benefit most, in the luxury segment mostly from Italy, France and Scandinavia. Trust is the magic word in the food sector for parents of just one child, and organic products made in Europe can benefit a lot from that. In the automotive and machinery sectors “Made in Germany” quality standards continue to sell well. Complex products like cars consist of components that are today produced in quite a number of EU Member States. This way, workers employed in factories in Romania, Czech Republic or Belgium also benefit from what is sold at the end as a top brand car from Germany or France. The failure to increase the low wages paid in Central and Eastern EU Member States, as well as the pressure on wages paid in supplying industries across Europe, translates now into a lost opportunity to increase resilience by lifting more family households in Europe into middle-income ranges, and hence improving the domestic demand side. It is high time for the EU to put much more effort on the social dimension of cohesion policy, on creating decent jobs and rethinking the organisation of value and supply chains in an economic structure guided by circular economy principles.

Demand in Asia is low for European products of lower quality, of less complexity or without a positive image. What can be produced in Asia today is already being produced there, and for a lower price due to the benefits of scale. You are most likely reading this text on a screen assembled in East Asia. World brands and international investors are heavily involved in production in China and Southeast Asia. The resulting lower consumer prices have made key information technology such as personal computers, smart phones, and flat screen TVs accessible to a historically high percentage of people living in the European Union, and other world regions. Against his background, decoupling our economies is neither an option nor desirable.

Additionally, we have to learn to live with the fact that Chinese enterprises are developing advanced technologies. In certain areas such as Artificial Intelligence, the EU ranks far behind China and the U.S., in particular with regard to applied technologies. Understanding the real needs of a global commercial and trade relationship that serves the achievement of the SDGs, we should not fall into the trap of attempts to decouple from the economic as well as the scientific cooperation with Chinese businesses. There is no need to underestimate or to fear China. We will depend on co-operation between European and Chinese companies to catch up technologically. The EU should reconsider its relationship with China and recent confrontational policy measures, such as the China country report by DG Trade. We should not emphasise a ‘rivalry’ in a hostile understanding, but instead develop a constructive concept to promote a partnership for contributing together to the solution to global challenges.

When rebuilding our economy from 2021, we should make best use of the opportunity for a consequent environmental and social transformation of our economies, together with our partners in the world, in order to achieve the United Nations’ SDGs by 2030, to mitigate climate change, to end hunger and to achieve peace. Trade policy should become an instrument of this transition.

Question 2: What initiatives should the EU take – alone or with other trading partners – to support businesses, including SMEs, to assess risks as well as solidifying and diversifying supply chains?

The Commission should together with the OECD, with Chambers of Commerce in the Member States, trade unions, and sectoral business associations offer trainings in supply chain risk assessment in line with the OECD guidance on supply chain due diligence.

The EU should enhance its circular economy capacities to reduce our dependence on raw material imports. This requires investments, including FDI, as well as regulatory initiatives such as a ban for non-recyclable plastics in food and beverage packaging.

At the same time, the EU should provide access to financing for building up processing industries in developing countries using modern technologies. The economic success of resource rich regions stabilises globally supply chains. That can offer a valuable option for EU’s SMEs offering such technologies to benefit from regional and local value chains in those economies and markets, too. Fair prices paid for goods from environmentally sound production under decent working conditions offer stability and predictability.

Question 3: How should the multilateral trade framework (WTO) be strengthened to ensure stability, predictability and a rules-based environment for fair and sustainable trade and investment?

The WTO must be at service for achieving the SDGs by 2030, and to safeguarding the common achievements. Obviously, this is asking for an agenda to set up a WTO reform process carried by all Members in an inclusive approach. All Members should be offered the opportunity to participate in the further development of a rules-based trade system benefitting their national, and regional interests, as well as the global agenda.

The WTO derives its strength from its dispute settlement system. No other UN institution has such a strong mechanism to enforce commitments made by its members or signatories to a convention. Time and experience have shown that the WTO dispute settlement mechanism is not perfect. Trust in the system is at the core of its functioning. The EU should hence start a new initiative together with the US and China, and strong partners from all continents, to prepare for a reform of the dispute settlement architecture. Maintaining a two-step system providing for appeal must be the precondition, though.

A reformed WTO brings commitments on trade and sustainable development into the scope of its dispute settlement mechanism. This should include a reference list of conventions from the UN system, composed with regard to achieving the 17 UN SDGs. The EU can share experiences gained with its GSP plus system, both positive and negative.

A reformed WTO institutionalises its cooperation with organisations that have developed a high level of expertise on sustainability issues, such as UNCTAD and ILO, but also UNEP, FAO, WHO, UNESCO and UNICEF. The European Union could set an example for this approach by setting up a regulator working group of its representatives in the UN system to streamline activities aiming at achieving the SDGs.

The WTO must accommodate measures by working groups of members wishing to move ahead faster on the road towards the SDGs, for instance by creating incentive systems for goods and services contributing to the SDGs, or by means of border adjustment systems for goods and services detrimental to achieving the SDGs.

The EU should promote actively the parliamentary dimension of the WTO, by strengthening the role and functioning of the Parliamentarian Conference of the WTO, as well as by introducing a footprint of parliamentarians into the rules-setting work of the WTO and the Ministerial Conference’s decision-making.

Question 4: How can we use our broad network of existing FTAs or new FTAs to improve market access for EU exporters and investors, and promote international regulatory cooperation – particularly in relation to digital and green technologies and standards in order to maximize their potential?

The question should be: how can we use what we have to achieve the SDGs?. This should contribute to the parallel reflection - in particular with the concrete strategies to deal with the Covid-19-pandemic - how to approach the need for social-economic restructuring of the EU’s and Member States’ economies. Penetrating foreign markets at all costs may not be the answer to other regions’ development needs. We should not create advantages for companies for the sole reason that they are based in the European Union. We should promote companies which can provide solutions to common challenges during the global transition towards sustainable economies. This has never been the benchmark of success for our FTAs.

Until now, the ex-ante environmental impact assessment of our free trade agreements was not done with the goal of improving the quality of our negotiation results. It took place, more or less, because people from outside the “trade world” demanded it. And it was done with the goal to demonstrate that the agreement in question does no harm. If you look, for instance, at the recent impact assessment for the EU-Mercosur FTA, you will find an author expressing again and again that measures by the Lula government against deforestation could prevent negative consequences from the agreement. There is a different government in place, legislation and finances to protect the forest are gone, and what happens on the ground is horrible. If one reads the facts in both the new and the older impact assessment carefully, the conclusion should be a different one: the free trade agreement between the EU and Mercosur will do harm, unless legislation is in place prior to its signature that will prevent harm or compensate for harm. This is important with regard to environmental consequences, as well as concerning social consequences for small farmers, and urban and rural workers. This is also important with regard to sustainability and competition. If a big landowner in Brazil applies large amounts of pesticides (which are banned in the EU but nevertheless exported to Brazil by EU companies) and pays his workers only with food and a roof over their head, the resulting products will be dead cheap. Importing such products into the EU is not only a health hazard for our population, it also makes smaller scale and organic farming in Europe uncompetitive. Trade would contradict achieving the SDGs.

We need an honest ex-post assessment of our existing FTAs to identify, in which aspects they have helped or harmed our new priority goals. The insights gained shall flow into the conceptualisation of our future agreements. The future generation of agreements are cooperation agreements to achieve the SDGs, including the important dimension of economic cooperation and trade.

Furthermore, it would serve the strict implementation of Human Rights related international obligations taken by the EU and Member States in the framework of the United Nations, for example the International Convention on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights as well as of Civil and Political Rights, or the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Question 5: With which partners and regions should the EU prioritise its engagement? In particular, how can we strengthen our trade and investment relationship with the neighbouring countries and Africa to our mutual benefit?

We are in one of those historic moments, when a new economic power is rising to its position in the world. In past centuries, such moments have often let to disaster, when the existing powers tried all economic and military means to defeat or at least contain the threat to their hegemony. The European Union should do all it can to find an intelligent way to accommodate the arrival of China on the world stage and to prevent a conflict between the People’s Republic of China and the United States of America. For this reason, priority must be given to cooperation with these two partners, and the third nuclear super-power, the Russian Federation. Furthermore, achieving the SDGs and avoiding a new rift in the global cooperation will not be possible without the active engagement of China, Russia and the U.S. A parallel major challenge is the future place of Africa in the world - taking into consideration the demographic developments on the continent and the impact on Europe and the EU, as well as the Middle East. It will become of massive importance for the EU’s re-shaping of trade and economic cooperation with all these partners for the next years.

We can build on our existing network of strategic partnerships in addressing the SDGs with priority. The EU has 10 strategic partnerships with Brazil, Canada, China, India, Mexico, Japan, the Republic of Korea (South Korea), Russia, South Africa, and the US. The EU also has strategic partnerships with two regions, namely the African Union, and the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC), and with NATO. While several important G20 partners such as Indonesia and Nigeria are still missing on this list, we should start to build with what we have. Originally driven by security interests and economic interests of the Union, priority should be shifted to achieving the SDGs by 2030. The EU is in the exceptional position of being capable of addressing all its partners in parallel in order to take-off with an orchestrated response to humankind’s major challenges. Commission and EEAS should jointly prepare a proposal for the respective re-design of the Union’s strategic partnerships.

Regarding cooperation with our Eastern neighbourhood, it is not enough to simply demand from our neighbours to take over our standards. Association agreements like the ones with the Ukraine and with Moldova, lack the concrete perspective of membership in the European Union. We should not continue with a neighbourhood policy, which is designed to institutionalise a centre-periphery relation, thus perpetuating the economic gap. Instead, we should expand socio-economic cohesion efforts beyond the Union’s borders. We should reach out with expertise, for instance by twinning projects, to help implementing the agreed state-of-the-art standards on the ground. Improved working conditions, improved environmental practice, improved animal welfare in the Ukraine and other neighbourhood countries are in the interest of the European Union and its citizens. We cannot continue to grant privileged access to, for instance, eggs from neighbouring countries that were produced by chicken living in conditions that are completely illegal in the European Union. Trade should not result in unfair competition for EU producers, which are trying hard to cope with environmentally sound standards, including animal welfare.

Regarding cooperation with our southern neighbourhood, we should endeavour for increasing job creation and intra-regional self-reliance. The key to a successful development in the region and a good relation with Europe is a massive investment in solar energy and production of green hydrogen in the sun-rich partner countries bordering the Sahara. Access to clean energy is key to the successful transition towards a climate neutral economy in Europe. But most of all, access to supposedly unlimited cheap energy will also spur sound economic development in Africa, in particular if combined with technologies for a decentralised harvesting of solar energy.

With its new approach of developing strategies with Africa, rather than for Africa, the EU should approach the AU with a proposal to seek and build an energy symbiosis. A landscape of cooperation projects should be designed to help the AU in rolling-out its ambitious pan-African model of the African Continental Free Trade Area, including free movement of citizens in the AU, and a common currency. A lot more effort is needed to jointly achieve the SDGs by 2030.

Question 6: How can trade policy support the European renewed industrial policy?

A renewed European industrial policy must be sustainable. Within the Conference on the Future of the EU, a deep discussion about challenges to establish a genuine EU industrial policy, a re-structuring of EU-Competition policy and the functioning of the correlation with Europe’s social dimension is necessary, and shall relate to the Trade policy review.

A central issue for transforming our industries, as well as for the parallel digitalisation, is access to clean energy. Our trade policy should develop a stronger focus on creating import opportunities for clean energy from regions with advantages in access to renewable energy, whether this is solar, wind, tidal, or thermic.

The ambitious goals of European industries to become climate neutral depend on access to clean energy. Hydrogen could become essential to transport energy. We need trade and cooperation agreements to swap knowhow against energy and make sure that the regions producing the clean energy benefit so much from it that they want to protect the supply chain themselves.

We should not shy away from public investment into new technologies. The added value of Europe can become visible when we invest together into research and plants in areas of Europe that could not effort such an investment themselves. Our negotiations in the WTO and with our bilateral partners must provide for the state subsidies needed to perform the environmental and social transition of our economy and our industry.

Recycling and reuse should become an important principle of EU industry. The EU could consider developing a tariff system that supports the transition. Tariffs on unprocessed raw materials should be increased to promote processing in developing countries, and to make the circular economy in the EU more attractive.

The modernisation efforts of our industries shall be protected from unfair competition through a carbon border adjustment system. Similar schemes can be imagined for other “badly produced” goods. The result should be trade offering incentives for Fair products, while balancing competitive disadvantages for sustainable ways of production in EU industry and agriculture.

This should not lead to an instrument used against unwanted competition for certain sectors of our industry. Europe cannot rebuild its economy at the expense of its partners. Benefits for sound production should be achievable also for non-EU producers.

Investment will be needed to finance the transition. The EU’s FDI control should have a focus on the quality of the investment, rather than the passport. Private equity investment often comes with obscene profit rate requests and had a very harmful impact on for instance newspapers, and on many well-functioning and profitable SME. Milton Friedman phrased in the 1970s “The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits.” Times have changed and this kind of investment should not be welcome in the EU. The Commission’s FDI Screening should report on investors that went against trade unions and labour rights, or did not respect environmental legislation.

Question 7: What more can be done to help SMEs benefit from the opportunities of international trade and investment? Where do they have specific needs or particular challenges that could be addressed by trade and investment policy measures and support?

The vast majority of SMEs is not yet involved in international trade. They would be best supported by developing local fairs to bring together producers and service providers in a county to set up co-operation. Promoting local supply chains, promoting consumption of local food, and promoting local services does certainly increase resilience, keeps means in the local economic circle, and eases the circular economy.

SMEs interested in exporting their products or services should find easy access to information about the respective rules and regulations. Ideally, the chamber of commerce in a Member State should be able to provide this information. This does not work equally well in all MS. The Commission should develop in close cooperation with the chambers and consumer protection organisations a multi-lingual web-based information tool to provide SMEs with the information they need.

The U.S. government is regularly offering webinars on e.g. how to do business in Japan, how to export to Brazil, etc. Together with the Chambers, the Commission should also engaging in providing information for EU SMEs on how to use the trade avenues open for them.

The Chinese are investing a lot in central and provincial trade fairs. This opportunity to meet and identify opportunities has been more common in the EU in the past as well. The Commission could help with analysis and international contacts to set up events in Member States, where SMEs are least involved in international value chains. At the same time, the EU delegations should provide assistance for doing business in Europe, in particular for Fair Trade companies.

Complicated markets are difficult to enter if a company lacks language capacities, cultural knowledge and local contacts. Joint ventures can offer all this. There are numerous positive examples for successful co-operation e.g. in China and in the U.S. The Commission could together with the Chambers offer information on best practice.

Trade is a lot about trust. Part of the job of the customs controls of any country is to make sure that an imported product may actually enter the market, and if so, at what cost. The increase of cross border trade and the booming online shopping makes this task ever more difficult. What can be done on the European side, before a product leaves the EU? The Commission should look into the options for establishing a clearing agency in support of export bound products. Compliance with rules of origin provisions, but also quality control could be a task. Companies should be able to qualify for the status of “trusted company” or “verified services”.

Many innovative SMEs encounter problems to receive a market approval for their products in third countries. The European Union should develop a trust-worthy independent quality control system and negotiate acceptance for such certified quality with partner countries. The current CE system is based on self-certification of producers and did not gain international trust.

All the above measures would also contribute well to the new due diligence approach of the European Union.

Question 8: How can trade policy facilitate the transition to a greener, fairer and more responsible economy at home and abroad? How can trade policy further promote the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)? How should implementation and enforcement support these objectives?

As stated above, achieving the SDGs should become the new benchmark of success for our policies, including our international trade policy. The SDGs are detailed in their structure, including the directly trade policy related goals. For instance, SDG 17 and its 19 sub-goals provide quite detailed instruction on what should be done to “Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalise the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development”. DG Trade should evaluate its own performance in regard to achieving the SDGs in an annual SDG report.

To support achievement of the SDGs, Fair Trade should become the new normal in trade. DG Trade should present a strategy to promote Fair Trade. Also, Due Diligence along our supply chains will help to ensure decent working conditions and environmentally sound production.

The EU must develop the ability to act against operators in trade that harm achievement of the SDGs. European consumers want to be able to trust their products. Europe must be able to close its doors for companies, whose production methods involve human rights violations, child labour, forced labour, exploitation of workers, theft of land, environmental crimes.

Question 9: How can trade policy help to foster more responsible business conduct? What role should trade policy play in promoting transparent, responsible and sustainable supply chains?

The proposal for a binding Due Diligence legislation announced by the Commission for early 2021 will support all EU based companies in gaining better control over their supply chains. Responsible business conduct is in the interest of each company and of each entrepreneur, whether it is with regard to local business relations or internationally. Fair Trade including respect for human rights, decent working conditions and environmental sustainability offers more stability in a supply chain than precarious trade relations and production.

The EU should offer complaint mechanisms for people negatively affected by EU companies. This would support the monitoring of the effectiveness of the due diligence approach.

The European Parliament will soon deliver a detailed legislative initiative report providing guidance for the Commission for the drafting of its respective legislative proposal. According to the expressed will of the Commission to accept a right to initiative of the European Parliament, it will become a decisive moment for the Commission to demonstrate honesty in its proceedings, while implementing and further developing the Inter-Institutional Agreement.

The Commission should aim for more coherence in related legislation. For example it should be prohibited to export pesticides which are banned in the EU, to third countries.

A legislative proposal should be considered to address auctions of contracts for suppliers that force the companies to offer unsustainably low prices which than in turn lead to unacceptable payment and working conditions in the supplier companies.

Europe’s financing sector should become an essential part of the transition towards responsible business conduct. Financing of unethical projects should be stopped. More transparency is needed for financing operations.

Question 10: How can digital trade rules benefit EU businesses, including SMEs? How could the digital transition, within the EU but also in developing country trade partners, be supported by trade policy, in particular when it comes to key digital technologies and major developments (e.g. block chain, artificial intelligence, big data flows)?

Block chain, AI, big data, quantum computing, Internet of Things, advanced robotics and Internet of Robotic Things, autonomous technologies, Real Deep Fake, face and movement recognition, different tracking technologies, Biotech and biohacking, are disruptive technologies. Their arrival happens faster than the development of an adequate international regulatory framework. In combination with new business models like platforms, the rules governing our trade arrive at their limits.

The European co-legislators have been able to address a number of important issues in recent years. Intensified work is now needed in the multilateral fora to agree on common approaches. In the past, decision making in multilateral institutions has been very slow. The Commission should come up with proposals to speed up the procedures, for instance by asking negotiators to meet more often, by escalating certain disputes to the political level, by introducing deadlines. We need to hurry up. Access to mass data is the starting point of the new technological revolution, and we must find the solution to make that possible without giving up the right to data privacy and other human rights. European legislation on data protection is state-of-the-art and we should be proud of it.

Block chain technology has a lot to offer to SMEs and developing countries, as it avoids the costs of intermediate operators. The Commission should, however, listen to the concerns expressed by Central Banks with regard to the consequences for currency control.

The arrival of the new technologies means also a steep increase in the energy demand. The step from 3G to 4G doubled the energy demand. The next increase is projected to be much higher. As described above, an opportunity exists to harvest solar energy in the sun-exposed regions of our planet. If managed wisely, this could lead to an economic boom for areas that have been disadvantaged for long. Trade has a role to play in making investment and technologies available that are needed for the transition.

Question 11: What are the biggest barriers and opportunities for European businesses engaging in digital trade in third countries or for consumers when engaging in e-commerce? How important are the international transfers of data for EU business activity?

To state it once again: trade is very much about trust. Data protection is not an obstacle to digital trade; it is a precondition to the success of digital trade. European consumers want to feel protected while being online. Therefore, international regulation for digital trade is welcome and necessary. The point of departure should be consumer protection. There is a need to ensure data privacy and to make consent the precondition for gathering of personal data. European companies operating in compliance with our high privacy standard should actively use this as an asset in marketing.

A technical problem emerges, as long as European companies – and even public authorities and police units - are forced to store data on servers outside EU jurisdiction due to a lack of European solutions available. The U.S. government, the Chinese government, the British government to name a few, have created legal access for their secret services to stored data, and even to data passing through internet knots, and have abused this technological opportunity in the past. Europe needs to develop the technological ability for cloud storage and transfer capacities within the jurisdiction of its data protection legislation.

Companies wishing to operate on the EU digital market should understand, respect and comply with the right to data privacy, as enshrined in the European Charter of Fundamental Rights. With regard to the roll-out of 5G networks, and with a perspective to 6G, the Commission should present a proposal for an EU-wide approach to require access to algorithms on demand to prevent abuse.

In the e-commerce agreement negotiations in Geneva, it is of high importance to maintain compliance with EU data protection legislation as a red line. The right to regulate must also be preserved with regard to future services and technologies.

Question 12: In addition to existing instruments, such as trade defence, how should the EU address coercive, distortive and unfair trading practices by third countries? Should existing instruments be further improved or additional instruments be considered?

The trade defence architecture of the Union works quite well when it comes to addressing unfair practices of states and governments. EU companies are confronted with unfair competition from individual companies reducing their costs by environmental dumping, exploitative employment conditions, counterfeiting, tax avoidance or fraud. There is too little cooperation between trade defence, violations of competition law, and criminal investigations.

The Commission should look into the options of how to address precisely certain companies and individual persons responsible more directly and quicker, for instance by black-listing for business operations on the EU market. Black-listing also CEOs could help to prevent a perpetrator from opening a company under a new name to continue his or her abusive economic activities. This would also help to address important indirect trade distortions, such as fraud, money laundering and illicit capital flows. At the same time, the Commission should look into the options for positive incentives for well-behaviour and good co-operation in the due diligence schemes, by awarding a “trusted company” status, which could, for instance, ease customs procedures as reward.

The Commission shall look into new forms of unfair competition in the digital economy.

The Commission shall finally address unfair competition practises in the financial services sector. Banks conspiring against tax authorities in e.g. cum-ex cross-border business operations are certainly distorting trade in financial services.

With regard to tax avoidance, there seems to be still too little consequences for European companies avoiding taxes abroad. The Commission should evaluate the reporting requirements established in EU directives. In the framework of policy coherence, the goal should be that EU companies pay their due share in tax income of partner countries, in particular in developing countries. The Commission shall also evaluate whether the established transparency rules have succeeded in reducing the involvement of EU companies in fraud and bribery abroad.

Concerning coercive practises of third countries, the EU should address the concrete cases more directly. We are talking about the U.S., and we need to talk with the U.S. and its new administration. With the Nord Stream related measures, the outgoing U.S. administration attempts to force their European allies to buy American gas instead of gas from Russia. Such blackmailing should result in the opposite. For domestic policy reasons, the outgoing U.S. administration re-enforced the economic blockade against Cuba. European companies trusted in the value of our bilateral agreement with Cuba, and are now running the risk to be punished for their engagement. This has to end. Cuba and the entire region, including Venezuela, need our support to overcome a deep crisis. On Iran, the U.S. sanctions have increased the risk of Iran developing nuclear arms. The Union must mediate and identify ways to improve Iran’s economic situation, which was the agreed price for the deal to end Iran’s nuclear programme.

With regard to the future, economic sanctions not covered by a decision of the UN Security Council should be an issue for an international court. In the process of the WTO reform also the scope of issues that can be presented to the dispute settlement system should be discussed.

Question 13: What other important topics not covered by the questions above should the Trade Policy Review address?

The TPR should address also the institutional set up of DG Trade. Restructuring is needed to prioritise the SDGs in implementing the reformed trade policy. The increased need for inter-institutional cooperation to achieve policy coherence should be better reflected in the Commission’s procedures. The current departments dealing with sustainability issues or under-staffed, there are too few people in charge of observing coherence.

Furthermore, improvement is still needed regarding transparency, and in particular, to keep both the European Parliament and Council equally well informed on the horizontal cooperation of various Directorates General of the Commission, as well as the EEAS and delegations abroad, about constructed clusters to deal with new complexities in the EU and in its external activities. Trade Policy must ensure to open trade agreements, as well as trading practices within other frameworks like e.g. the Union’s GSP mechanism, towards the gender dimension. Equally important is to enhance the permanent involvement of civil society representation into the implementation and monitoring of trade policies. In order to achieve this, it is of high importance to strengthen the role of Domestic Advisory Groups in bilateral and bi-regional Trade Agreements, including the financing of their work and meetings of DAGs of our partners from the EU budget.

Schlagwörter

- Artikel teilen

- Zum Seitenanfang